Seedstock Sector Represents Both Beginning & End Of Beef Production

Decisions made by seedstock producers today determine the potential for satisfying beef consumers three years down the road.Read part one in the yearlong Connecting The Dots series here.

August 29, 2012

At its simplest, the seedstock sector represents both the beginning and the end of beef production. It provides the genetics utilized by commercial cattle producers to build market calves for harvest, as well as replacement females to replenish the commercial cow factory. Seedstock producers also provide the genetics they and their peers will use to build the next generation of seedstock.

Ideally, seedstock production also represents the final link in the production chain, as producers survey successes and failures based on economic signals received by them and their commercial customers, and adjust the genetic potential.

That’s where it gets complicated.

Even when economic signals are clear – and some would argue they never are – mating decisions for seedstock today cannot result in commercial use for at least two years; and market results can’t be known for at least three years.

What goes into mating decisions represents an attempt to find balance amid a chaotic array of data. There are weights, measures, EPDs, indices, various DNA profiles, pedigrees, inbreeding coefficients, etc.

Learning and sorting through this complexity is all the more remarkable when you remember that, in relative terms, modern seedstock production – modern beef production for that matter – is still in its infancy.

“Distinct breeds did not emerge until the second half of the 18th century when the industrial revolution in Europe created a need for more productive animals,” writes Harlan Ritchie, Michigan State University distinguished professor of animal science, in his book, “Breeds of Beef and Multi-Purpose Cattle.”

“More than any other single factor, the need to feed workers of the newly created mills and factories was responsible for the advent of modern breeds and breeding practices…It is probably not an exaggeration to state that the industrial revolution spawned the cattle revolution…,” Ritchie writes.

Consider that Hereford and Angus cattle came to the U.S. in the late 1800s. Research aimed at beef cattle didn’t started until the early 1900s. And the modern U.S. beef industry, built upon cheap corn and energy, didn’t start taking shape until after World War II. Technology to successfully freeze and thaw semen didn’t debut until the 1950s, and the Continental breeds didn’t show up in the U.S. until the 1960s.

If you ever wonder how successful seedstock producers have been in harnessing evolving technology, check out the genetic trends; some breeds have literally transformed themselves in less than two decades.

Successful seedstock producers

Charged with both anticipating and reacting to market signals and customer demands, it’s easy to understand why the most successful seedstock producers are those who understand the cattle business end to end. They know what drives customer profitability, as well as the marketability of their customer’s calves, whether sold at weaning, retained through the stocker pasture or retained clear through finishing.

“The challenge for commercial cow-calf producers is finding genetics that will complement their cowherds in their unique environments, while maintaining or reducing costs, and adding value to the calf crop at the same time,” says Bob Prosser of Bar T Bar Ranch, based at Winslow, AZ. “Simple as that sounds, making it happen depends on forging a relationship with a seedstock producer who is committed to helping his customers reduce costs, add value to their product, and increase marketing opportunities while producing a quality product for the end consumer.”

The Prossers serve as an example of seedstock producers based in commercial production. In addition to their seedstock herd, they maintain a commercial one. They run stockers, feed cattle, and are involved in value-added branded beef programs.

Demanding customers

The only customer a commercial producer must face is the sale barn or order buyer. If seedstock producers are going to stay in business, they must face a lot of customers and prospective customers, all with different personalities, goals, resources, wants and needs.

Bull buyers can be a fickle lot, too. They’ve been known to cuss breeders for selling them bulls that melt in the pasture when turned out the first time because they were over-conditioned. Then they’ll go buy fat bulls again next year because they are more appealing to the eye than harder, pasture-ready ones.

Industry Resource Page: Bull Management

Of course, seedstock producers can be a fickle bunch, too. Some have been known to single-trait select for the purposes of marketing at the expense of balanced production.

“The seedstock sector is at a crossroads where more than superior pedigrees and outstanding EPDs will be required,” Ritchie said in his 2000 paper, “Where is the Beef Seedstock Industry Headed?”

“Commercial customers are continually expecting more from their genetic providers. In order for mainstream seedstock breeders to ensure their sustainability well into the future, it will be necessary that they strive to become full-service genetic providers,” Ritchie says.

My View From The Country Blog: Where's The Seedstock Sector Headed?

Though seedstock producers of all sizes are successful, selection dynamics, production and marketing costs, and customer service favor larger seedstock herds. That doesn’t mean the same herd, necessarily; alliances between individual herds offer similar advantages.

Richie explains, “A number of seedstock producers have already positioned themselves as full-service providers. The services they offer are similar to those provided by the genetic companies and mainstream independent breeders in the swine industry.”

Seedstock opportunity

Adding to the challenge of seedstock production is the simple fact that demand is always limited by the size of the commercial cowherd.

In 2006, there were 33.25 million beef cows that calved, according to the National Agriculture Statistics Service (that year is chosen for context with the breed numbers that follow). If you figure a bull for every 25 cows – excluding those bred artificially – there was a need for about 1.33 million bulls. If you figure a fourth of that requirement needs to be replaced each year, about 332,500 bulls needed to be marketed that year.

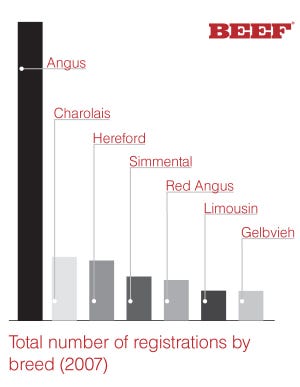

In round numbers, 17 of the most populous beef breeds registered 765,038 bulls and females in 2007, according to the National Pedigreed Livestock Council. (That’s the most recent year in which all of the seven most-used breeds reported registration numbers. The movement of some breed associations to whole-herd reporting has made year-to-year comparisons more tenuous.)

In round numbers, 17 of the most populous beef breeds registered 765,038 bulls and females in 2007, according to the National Pedigreed Livestock Council. (That’s the most recent year in which all of the seven most-used breeds reported registration numbers. The movement of some breed associations to whole-herd reporting has made year-to-year comparisons more tenuous.)

Of those registrations, 86% came from seven breeds, which speaks to the ongoing breed consolidation that began at least 15 years ago.

Ritchie proved prescient more than a decade ago when he predicted: “Very few of the 50-plus beef cattle breeds in the U.S. will disappear, but they will likely sort into three groups:

10 breeds, or perhaps less, that will provide the genetic make-up of the bulk of the commercial cattle population;

a few breeds having unique attributes that will be involved in niche markets;

recreational breeds that will provide pleasure and entertainment to hobby breeders via shows, field days, etc.”

Keep in mind, these numbers cannot account for unregistered seedstock. That includes commercial producers who find a cracking good calf to sell to the neighbors, as well as large entities currently crafting a model of seedstock production and marketing that mirrors that of the swine industry.

“Seedstock producers must produce genetics specific to commercial cattlemen’s needs, while meeting the specific requirements of the feeder, packer and retailer,” Prosser says. “This is not to be construed that every seedstock producer must produce cattle that will fix each and every commercial cattleman’s problem. Rather, it means that responsible seedstock producers must forge relationships with commercial customers to identify opportunities and assist in finding solutions.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)