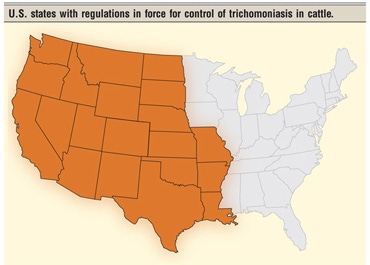

Trichomoniasis Is Spreading Across The U.S.

Trichomoniasis continues moving north and east.

November 1, 2011

When Craig Payne, DVM, was in private practice and encountered a herd with too many open cows, trichomoniasis (trich) was on his checklist of possibilities, but it was down toward the bottom. He hardly ever encountered this bovine venereal disease in Missouri.

When Payne visits with his colleagues around the state today, as a University of Missouri Extension DVM, he says trich is moving up on that checklist.

“Is trich a growing problem or are we just finding more of it because we’re testing more? I think both answers are correct,” Payne says.

Tommy Barton, DVM and director of the Texas Animal Health Commission’s Region 7, concurs that trich is a growing problem. “And, the frequency of its detection is being brought about by producer education and more testing by producers in order to protect their herds,” he adds.

Nationally, prevalence data for trich is a hodgepodge of studies conducted in various states across the decades. Jeff Ondrak, a DVM at the University of Nebraska’s Great Plains Veterinary Education Center, summarized a dozen of them. Among those he cites as the most reliable, 15.8% of test herds in California had a least one bull infected with trich, and 28.8% of Florida operations.

None of the studies are from states where trich diagnosis has increased, however. In states like Missouri, Arkansas and Texas, trich regulations have been established or revised in recent months for both intrastate and interstate bull movement.

In Missouri, for instance, beginning Sept. 1, eligible bulls moving intrastate must test negative for trich before changing ownership or possession. Prior to that, regulations only accounted for bulls coming from other states. Between March 1, 2010, and Aug. 31, 2011, trich had been diagnosed in 39 counties.

As of the end of August, Texas no longer accepts virgin breeding-age bulls into the state without a test.

Arkansas already had regulations aimed at interstate bull movement. After finding 20 cases of trich in six months, the Arkansas Livestock and Poultry Commission enacted an emergency measure in June requiring a negative test for intrastate bull movement, too. That regulation has since been made permanent.

If you’re unfamiliar with it, trich is a venereal disease caused by a protozoan that can cause abortion, early embryonic death or temporary infertility in cows and heifers. The primary mode of transmission is via infected bulls, though cows can be carriers, too. Once infected, bulls (especially those three years old and older) are typically considered to be carriers for life. Following abortion, infected cows usually begin ridding themselves of the infection. That’s why most regulations are aimed at bulls.

“Data suggest that the average percentage of open cows in a trich-infected herd will be 30%-50%,” Payne says. At one end of the spectrum, the infection can be ruinous. At the other, the lost pregnancies and late calves associated with trich can be almost invisible, yet rob the herd of reproductive performance.

“It doesn’t have to be catastrophic to be costly,” Payne says.

Prevention varies by operation

“I think producers have to take responsibility for protecting their herds,” says Tom Troxel, University of Arkansas animal science professor. “I tell Arkansas producers to isolate and test bulls they’ve purchased, even if those bulls have been tested within 30 days of delivery. You don’t know where they’ve been since they were tested.”

Troxel recommends testing bulls before they’re turned out with the cows, and again following breeding season. It’s also important to maintain good breeding records and know which bulls were with which cows, he says.

When it comes to testing bulls currently in the bull battery, Payne believes, “producers and their veterinarians need to make that decision together because of the dynamics that exist in each situation.”

For instance, Payne says, if reproductive rate is within acceptable limits and there are no reasons to suspect the disease was introduced, the decision might be to forego a test. Conversely, if the producer is surrounded by neighbors with leaky fences and a revolving bull lineup, the decision might be to test on both ends of the breeding season.

Cost for the test varies with the laboratory and volume. For a broad ballpark, figure $25-$50/head. That doesn’t include the vet charge or shipping costs.

There are ways to minimize testing costs, however. In Arkansas, Troxel says some producers cooperate to get their bulls tested at the same time in the same location.

As for bringing open females into the herd, Payne believes trich prevention strategies boil down to risk tolerance. You could test the cows, but he says veterinarians typically reserve testing for special circumstances, such as an abnormally high percentage of open cows in a situation where the bulls that bred them are no longer available to test.

Plus, Payne points out testing cows is a challenge because the more time that’s passed since exposure, the more unlikely you are to find it in the cow. That’s because the number of organisms decline rapidly after a cow aborts.

“The rule of thumb is that if an open cow hasn’t been exposed to a bull for 120-150 days, then the chances of trich being present are reduced,” Payne explains. So, those who are risk averse and buying open cows could wait that long to breed them.

Vaccinating cows

You can vaccinate cows against trich, but it’s operation dependent, Payne says. “It isn’t a substitute for biosecurity and good management practices; it’s a tool that is available. Some data suggests the vaccine won’t necessarily prevent infection, but can increase calving rate. Used across the herd, it may prevent catastrophic losses if administered prior to the introduction of the disease,” he says. Again, this decision should be made by producers with their veterinarians.

“Another alternative is to breed them with a bull you don’t let breed other cows, using that bull as a sentinel,” Payne says. In other words, if the bull tests negative going in and coming out, the cows are clean.

“Or, you can just throw caution to the wind,” Payne says. He doesn’t mean that facetiously, either. Besides the low prevalence rate overall, there can be sound reasons for believing trich risk is negligible. Payne stresses that producers and their veterinarians should work together to choose the appropriate strategy.

Troxel emphasizes solid management mitigates the risk. “Have good cow and calving records and a tight calving season so that you can recognize the symptoms of trichomoniasis early.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)