Veterinarians Must Play Key Role In Expanding America's Cowherd

Veterinarians are integral to the beef industry’s necessary expansion.

August 29, 2014

As beef producers in the United States move to expand numbers, veterinarians are positioned to play a key role in the process of rebuilding the U.S. cow herd,” says David Patterson, state beef extension specialist and professor of animal science at the University of Missouri (UM). Patterson is also an internationally recognized expert in beef cattle reproduction.

“Veterinarians serve as a key information source for U.S. beef producers and are essential in facilitating the adoption of reproductive procedures,” Patterson says. He refers to the beef 2007-2008 study from the National Animal Health Monitoring System (NAHMS). It cites veterinarians as the primary source most cow-calf producers use as their source for information pertaining to their operations, including health, breeding and genetics, nutrition or questions pertaining to production or management.

This trust represents a key veterinarian opportunity and responsibility as the industry faces the need to significantly grow the cow herd.

Wanted: Reproductively Fit Heifers

For perspective, when this year began, there were 29 million beef cows, according to USDA. In 1996, 18 years earlier, there were 35.3 million. All cows and heifers calving last year were the fewest since 1941. The total inventory of all cattle and calves January 1 this year was the sparsest since 1951 at 87.7 million head.

In its 10 year projections published earlier this year, USDA estimates a beef cow herd of 33.7 million head by 2023—4.7 million head more than we had when 2014 began.

The annual U.S. Baseline Briefing Book released by the Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute (FAPRI) at the University of Missouri sees beef cows increasing from 28.9 million head this year (January 1) to 30.9 million head in 2018, and then declining to 30.1 million head by 2023—as many as 1.1 million more cows over the next decade.

According to Patterson and D. Scott Brown, a UM agricultural economist and assistant research professor of agricultural and applied economics, “The opportunity for an increase in retention of beef heifers to exceed 5 million head remains a possibility as the herd attempts to recover from the long term inventory decline.”

D. Scott Brown, University of Missouri Ag Economist

Besides growing raw numbers in the name of competitiveness with other domestic animal protein sources, and with international beef, U.S. beef producers also need to improve the reproductive efficiency of the existing herd.

Based on a synopsis of key efficiency metrics from Southwest Standardized Performance Analysis, such as calving rate and pounds of calf per cow exposed, efficiency during the past two decades is static at best.

“Effecting change in reproductive management of the U.S. cow herd requires a fundamental change in the approach to management procedures and development practices being used on heifers retained for breeding purposes,” Patterson and Brown say. “We have reached a point concerning reproductive management of our nation’s beef cow herd in which the tasks of development and transfer of technology must be emphasized equally and progress parallel to one another for the U.S. to maintain a strong beef cattle sector in our agricultural economy. Unless efforts are taken to implement change and incentives in the U.S. beef cattle industry, many of the products of our research and technology will be exported to more competitive international markets.”

David Patterson, State Beef Extension Specialist

Unfortunately, the NAHMS study mentioned earlier suggests the use of reproductive technologies in U.S. commercial beef cow operations continues to be lacking. In that survey, for the East and South Central regions, Patterson points out only 22 percent and 32 percent of beef cow operations, respectively, used reproductive procedures including estrous synchronization, artificial insemination, pregnancy diagnosis, ultrasound, pelvic measurement, body condition scoring, semen evaluation, or embryo transfer. In the West and Central regions it was 55 percent and 49 percent, respectively.

For that matter, 55 percent of beef operations in the U.S. reported having no defined breeding season, representing 34 percent of all beef cows in the U.S.

One reason adoption of readily available reproductive technology lags is the fact that so many producers have so few cows.

Fragmented Cow Herd Structure Represents Challenge and Opportunity

In round numbers, 3.58 percent of the operations in the 2012 Census of Agriculture had herds of 200 or more cows, representing 32.6 percent of all beef cows. At the other end of the spectrum, 57.2 percent of all operations had herds with 19 or fewer cows, representing 11.37 percent of all cows.

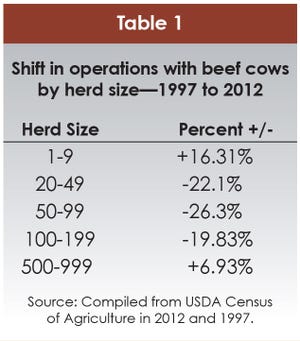

This distribution of fewer and larger operations controlling relatively more cows than smaller and more numerous operations is nothing new. What becomes more apparent when comparing the latest census to the one in 1997—in order to account for most of the years of cow herd liquidation—is the transition of the operations in between with herd sizes of 20 to 99 head, as well as those with herd sizes of 100-299 head (Table 1).

For perspective, there were 76,589 fewer beef cow operations (-9.52 percent) in the 2012 census than in 1997 for a total of 727,906 total operations with beef cows. There were 5.1 million fewer beef cows (-15.0 percent) in 2012 than in 1997 for a total of 28.96 million cows.

For perspective, there were 76,589 fewer beef cow operations (-9.52 percent) in the 2012 census than in 1997 for a total of 727,906 total operations with beef cows. There were 5.1 million fewer beef cows (-15.0 percent) in 2012 than in 1997 for a total of 28.96 million cows.

Most of the attrition among operations—not counting herds with 2,500 or more cows—occurred for those with 50-99 head. There were 25,408 fewer of these operations (-26.30 percent) in 2012 than in 1997. Herds with 50-99 head accounted for 1.65 million fewer cows (-25.85 percent) in 2012.

Operations with 20 to 49 head decreased by 50,449 (-22.1 percent) to a total of 177,658 operations in 2012. These accounted for 1.52 million fewer cows (-22.19 percent) than in 1997 for a total of 5.33 million head.

Operations with 100-199 cows declined by 19.83 percent. There were 9,011 fewer of these operations in 2012 for a total of 36,428 operations. These operations accounted for 1.11 million fewer head (-18.82 percent) than in 1997 for a total of 4.80 million cows.

There are plenty of reasons for the attrition among these operations or for the movement of operations with larger herd sizes to smaller ones. Among them are likely raw economics and the need for an operation deriving a significant portion of its annual income from cows to have more cows in order to dilute costs and risk. It’s that risk that is becoming more untenable for some producers with cow-calf enterprises who also have jobs off the farm or ranch.

These same factors could help explain why operational growth, on a percentage basis, occurred among herds with one to nine head. There were 36,593 more of these operations (16.31 percent) in 2012 for a total of 261,017 operations. This group also accounted for 83,396 more cows (+7.46 percent) in 2012 for a total of 1.20 million head.

The next most growth occurred among herds with 500 to 999 head. There were 273 more of these operations (+6.93 percent) in 2012 and they accounted for 176,590 more cows (+6.94 percent) than in 1997 for a total of 2.72 million head.

As for the operations with 2,500 or more cows, there were 168 in 2012, which were 44 fewer (-20.75 percent) than in 1997. They accounted for about 696,000 cows, which was 26.29 percent fewer.

Plenty of Reproductive Tools Exist

“Moving forward, the veterinary community and allied industry will be required to take on larger roles in supporting beef producers in understanding the benefits of incorporating improved technologies into management schemes on the farm or ranch, and that benefits derived from these technologies outweigh their costs,” Patterson says.

There are plenty of tools to choose from, too.

“There now exist an array of technologies currently online or emerging that offer the potential to expedite genetic progress, enhance efficiencies of production, and add value to beef cattle produced in the U.S.,” Patterson explains. “Improvements in reproductive technologies have enabled beef producers to utilize artificial insemination without the need to detect estrus; existing and emerging genetic and genomic technologies enable beef producers to make more rapid strides toward improving the quality of beef they produce; and producers’ ability to access and target individual marketing grids enable them to be rewarded for specific quality endpoints.”

Subscribe now to Cow-Calf Weekly to get the latest industry research and information in your inbox every Friday!

“On-farm development programs that involve local veterinarians, state, regional, or county livestock specialists, and individual farm and ranch operators provide the structure from which change within the industry can occur,” Patterson emphasizes.

Specifically, Patterson explains veterinarians are critical components in implementing what he describes as a five-point plan to improve beef cow herd sustainability.

1. Create an understanding of the importance of heifer development based on reproductive outcomes.

2. Implement changes in heifer development that will eventually spill over into the cow herd.

3. Emphasize the importance of reproductive management, which becomes apparent as changes are implemented.

4. Expand producer focus to genetic improvement.

5. Emphasize to participating herds that creation of a value added product requires a reevaluation of marketing strategies.

These were the steps developed in 1996 by veterinarians, extension specialists, beef producers and allied industry in Missouri to implement a plan that would impact long term sustainability of beef herds across the state. These steps also serve as the core to the Missouri Show-Me-Select Replacement Heifer Program, which other states are attempting to emulate.

“These five steps have built equity in herds that embraced the plan, and 16 years later the Missouri Show-Me-Select Replacement Heifer Program has impacted the cattle industry statewide,” Patterson explains. “The program incorporates all available tools to support long term health, reproduction, and genetic improvement of replacement beef heifers and includes provisions for ownership; health and vaccination schedules; parasite control; implant use; weight, pelvic measurement and reproductive tract score; estrous synchronization and artificial insemination; service sire requirements for birth weight EPD or calving ease EPD; early pregnancy diagnosis, fetal aging, fetal sexing, and body condition score.”

Incidentally, much of this information, and more, is part of a recently published abstract, “Management Considerations in Beef Heifer Development and Puberty.” It is published in Clinics Review Articles at Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice.

“This compendium provides a comprehensive overview of the various considerations involved with successful development of replacement beef heifers,” Patterson explains. “It is intended to serve as a resource for veterinarians to support beef producers in better managing their herds and to rethink the way in which heifers are developed as they enter herds across the U.S.”

Increasing Equity Risk Demands Finer Reproductive Focus

The importance of all of this will likely accelerate, too

“As cattle prices and input costs increase, traits of efficiency and quality will be become bigger drivers of profitability than ever before, and the commodity model of U.S. beef production in all likelihood will no longer be viable,” Patterson and Brown say. “Beef producers in the U.S. have the tools in hand to maintain our country’s ranking as the leading global supplier of high quality beef. As U.S. beef producers look to the future, the challenge most will face centers on determining which, if any, of these tools will be adopted and used to the extent that enables current and future generations to compete in a global arena, and if so, how effectively.”

Future issues of BEEF Vet will explore the reality of specific opportunities that current expansion presents to veterinarians to help their clients improve the reproductive efficiency of existing herds, select and develop heifers and sort through the economics of keeping or buying replacement heifers.

“A range of procedures are available to cow-calf producers to aid in reproductive management of replacement beef heifers and determine the outcome of a development program. These procedures, when viewed collectively as a ‘program’, assist producers in more effectively managing reproduction in their herds,” Patterson says. “One can assume that a very small percentage of either raised or purchased replacement heifers are ‘programmed,’ per se, in terms of reproductive procedures currently available. The expertise to develop and market programmed heifers exists, but requires a team approach to manage heifers from the perspectives of health, nutrition, reproduction, genetics, and emerging management practices.”

Other trending headlines at BEEF:

Why Is Death Loss Increasing In Heavier Beef Cattle?

Readers Share Their Favorite State Fair Memories

Photo Gallery: 10 New Farm Trucks To Consider For 2014

Why The Movie Noah Upset This Rancher

Feedlot Tour: Triangle H Grain & Cattle Co.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)