The beef industry may be approaching a practical limit on carcass size, but that is not so much driven by the concern over ribeyes too big for a plate.

September 26, 2012

Cattle feeders don’t like $7 or $8 corn, but they know what to do at those higher prices. Most of them feed cattle longer to heavier weights and sort them to market on a grid.

Maybe not all cattle feeders see it that way, but in the big picture, that’s what is happening, says Shawn Walter, president of Professional Cattle Consultants (PCC). He presented “How big can we go?” at last month’s Feeding Quality Forum in Grand Island, Neb., and Amarillo, Texas.

“Every few years we talk about it, can we make carcasses any bigger? Well, we keep doing it,” he said, noting one of many graphs. “This is never a straight line, but we’ve had an upward trend for carcass weights since the 1960s all the way through the current year.”

You might wonder why, unless you think about how the market gets what it pays for. Packers have been paying for more pounds.

Walter studied historical carcass-weight data for steers and cows and surmised the first wave of steer increases came from crossbreeding.

“During the ’60s and ’70s, we had those increases in steer carcass weights without changing our cow size much,” he said. “However, as we got into 1980s, we saw more of the Continental crosses retained as females and in that decade, cow weights increased faster than steer weights.”

The next decade saw a boom in growth technologies in the feeding sector, especially trenbolone acetate (TBA) implants. Grid marketing developed a weight range that discounted outliers – but the upper limit has stair-stepped as both cow and steer weights keep trending higher.

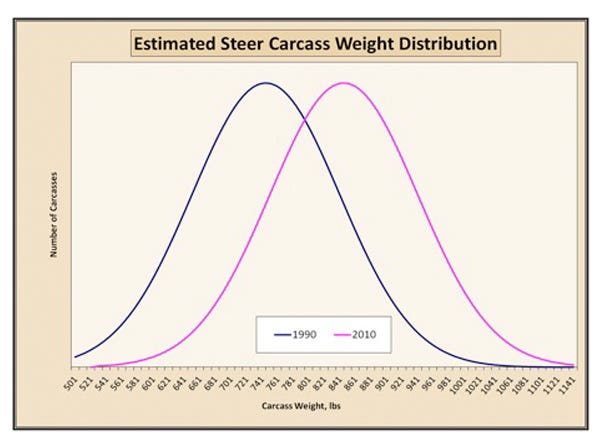

From 1990 to 2010, the heavyweight carcass limit moved from 900 lb. with 5% of steers heavier at the start, to 1,000 lb. and 4.1% exceeding those limits by 2010 (see Figure 1). Some U.S. grids have moved up to a 1,050-lb. limit now.

“We have increased the production, the genetics and the growth in our cowherd,” Walter said. “This train is headed down the tracks with a pretty good head of steam and to just turn that around is not likely. Bigger cows equal more dollars per calf, but profit? That’s an operation-by-operation question.”

Feedlots have economic pressure to maximize weight potential from those calves, once they cross the threshold to grade-and-yield pricing. Gridded cattle tend to push up against the heavyweight discount limit, while cash cattle find their way to market at the earliest possible date to cut down on feed costs.

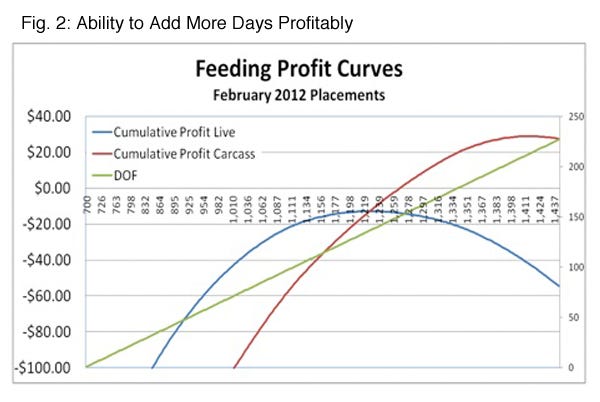

That’s because of the differing profit dynamics between cattle in those two marketing channels, Walter explained (see Figure 2).

Using a PCC model based on cattle placed at 750 lb. this February, live cattle sold on cash bids start losing money before 130 days on feed or 1,200 lb., but cattle could be fed for a couple more months to add 180 lb. for value-based marketing.

“The incremental cost of gain on a carcass-weight basis towards the end of the feeding period is more efficient than live-weight gain, with 80% of it going to carcass gain by then,” he said, noting that phenomenon is known as “carcass transfer.”

As more cattle feeders realize this, fewer sell cash live cattle and demand increases for the kind of feeder cattle that will grow and grade. Pressure also mounts for the use of more aggressive growth technologies and strategies that can help improve feed efficiency, Walter added.

“Sorting to top off pens for the grid and putting the rest on a beta-agonist ration can result in more pounds with less heavyweight discounts. When the corn price doubles, the ROI on these strategies doubles,” he said.

The beef industry may be approaching a practical limit on carcass size, but that is not so much driven by the concern over ribeyes too big for a plate. Innovations in beef merchandizing have stepped up to that plate, and larger size is actually an advantage for some cuts. Boxed beef offerings may adjust to better sort for similar size cuts.

Rather, the limit has to do with plant equipment, human labor and how much weight the workers can easily handle in fabrication and processing, Walter said.

Still, packers have incentive to increase average weights as the number of carcasses declines, he added. “I don’t know that we have seen the economic signals telling us to limit carcass weights, so we’ll keep making cattle and carcasses bigger to be more efficient.”

The meetings were sponsored by Pfizer Animal Health, Certified Angus Beef, Purina Land O’Lakes and Feedlot Magazine.

You May Also Like