An ongoing Oregon study assessing wolf-cattle interaction and its impact on cattle behavior is delivering some insightful results.

September 30, 2013

The West’s growing wolf population is significantly impacting ranchers and livestock, but to what extent hasn’t been well-documented. That need is being addressed by a 10-year study funded by the Oregon Beef Council (OBC), with help from USDA; some of the early results are surprising.

Begun in 2008, the study uses GPS collars on cattle in the study area — and on a few wolves. The collars allow researchers to monitor movements of these animals, and when and where they interact.

Pat Clark, range scientiest at USDA’s Northwest Watershed Research Center in Boise, ID

Range scientist Pat Clark of USDA’s Northwest Watershed Research Center in Boise, ID, has been involved with the study since its inception. Clark attracted the attention of OBC, which learned he was using GPS collars to collect data on the wolf-livestock issue in central Idaho. Doug Johnson from Oregon State University had also been doing GPS collar work on range cattle in northeast Oregon with a collar design of his own.

Figuring it was only a matter of time before wolves extended their range into Oregon from Idaho, OBC wanted to evaluate how wolves would impact rangeland cattle production in Oregon. So OBC asked Clark and Johnson to extend Clark’s wolf-cattle interactions research to northeastern Oregon (where there were no wolves yet), and western Idaho (where wolves were common).

Thus, the Oregon/Idaho Wolf-Cattle Interactions Project began with three study areas each in western Idaho and in eastern Oregon.

“We selected Idaho study areas from the western part of the state, where range-cattle grazing is the dominant land use, and where wolves were common. We searched for sites in Oregon with similar topography, vegetation types, soil types, cattle breeding, calf age at turnout, grazing schedules, etc.,” Clark explains. Wolf presence was the main differing factor between the Oregon and Idaho sites.

“This type of experimental design is called a BACIP [before-after/control-impact, paired] design. The Idaho study areas served as the control, since wolves were already present. What would eventually change [and create impact] was wolf presence in Oregon. Wolves were expected to travel from Idaho into Oregon and establish packs in the Oregon study areas,” Clark says.

The researchers wanted to collect at least two years of data in Oregon before wolves arrived in sufficient numbers to exert a true impact. They could then contrast that data to data collected after wolves extended their range into Oregon.

“We put GPS collars on at least 10 cows in each study area. Herd sizes in these areas ranged from 300-450 cows. The sample size was limited by available funds from OBC,” Clark says. The study was later expanded to two more ranches, giving enough sample size for adequate data to detect differences in cattle range use and other behaviors.

Interested in more practical cattle news? Subscribe NOW to Cow-Calf Weekly for information straight to your inbox every Friday!

GPS data track the location of collared cows and determine how fast they travel. “From this, we can calculate how much time a cow spends foraging during the day, vs. standing looking around, or resting. A hyper-vigilant animal spends a lot of time standing watch, rather than foraging, which could impact nutritional status. With GPS data collected every five minutes, we can detect changes such as increase in vigilant behavior and decreases in foraging time,” Clark says.

One of the Idaho study sites is the OX Ranch near Council, ID, managed by Casey Anderson, where data have been collected since 2008. The ranch experienced wolf predation before the study started, but had no documentation. “In 2009, we were able to confirm more of the wolf kills — 18 animals. But five cows, two yearlings, a bull, and about 70 calves also were unaccounted for,” Anderson says.

There were few wolves in Oregon when the study began — just those passing through and returning to Idaho. Within two years, however, the wolves established packs in northeastern Oregon, and the study moved into the “after” phase: comparing high wolf pressure with low wolf pressure (rather than no wolf pressure).

Researcher study the indirect effects of wolves on livestock range-use patterns impact foraging efficiencies, disposition and stress levels.

Tracking interactions

“Having wolves and cows collared enables us to match up their location and time, and determine where and when wolf-cattle interactions are occurring,” Clark says. Data on wolf presence and activity are augmented by wolf scat sampling along forest roads, and use of trail cameras.

Though only one wolf was collared in 2009, the results proved interesting. “We found interactions between all 10 of the collared cows and that single GPS-collared wolf within a very extensive study area [over 50,000 acres]. The 10 collared cows were part of the larger herd of 450 cow-calf pairs, yet the data showed this wolf was within 500 yards of every one of the 10 collared cows many times throughout the summer [for a total of 783 contacts],” Clark reports.

In fact, the collared wolf’s area was 210 square miles, with a 55-mile perimeter. The least distance he traveled was six miles/day, and the most was close to 29 miles/day. “On a day of confirmed predation, we could look back to the data and see that the wolf was in the immediate area at that same time,” he says.

This wolf was part of an 11-animal pack. There were three different packs, totaling 34 wolves, roaming that study area during 2009. The producer in that area suffered more than 40 confirmed or probable wolf depredations.

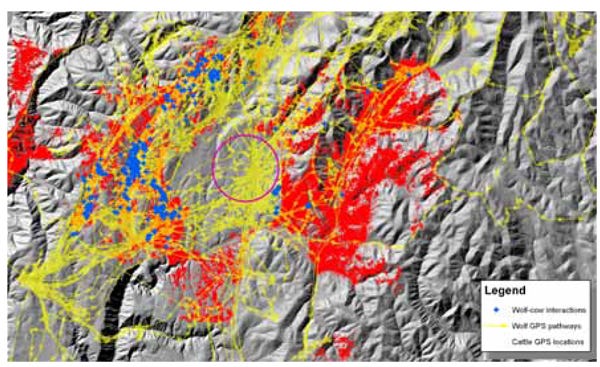

Resource selection patterns of 10 GPS-collared beef cows (shown as red dots), representing a herd of 350 cow-calf pairs, and movement paths of one GPS-collared wolf (shown as yellow arrows), representing a pack of 11 wolves, are all illustrated relative to wolf-cattle interactions between these 10 collared cows and 1 GPS-collared wolf (shown as blue crosses). A wolf-cattle interaction was defined as where a collared cow was located within 500 meters (about 547 yards) of the collared wolf, and when the cow and wolf locations were temporally separated by less than 15 minutes. The area highlighted with a purple circle represents a pasture occupied by uncollared beef cattle that are managed separately from the study herd.

The collared cow with the least number of interactions with the collared wolf had 23 interactions within 500 yards during that grazing season. One cow encountered that wolf 140 times (at less than 500 yards) over the course of 137 days (mid-June through early November 2009). All 10 collared cows had interactions within 250 yards, and nine cows had interactions at 100 yards or less.

Envision 450 cows with more than 30 wolves moving among them. If one wolf had 783 encounters with just 10 of those cows, how many encounters might there have been with 30 wolves among the 450 cows? In other words, the cattle were constantly being affected by the presence of wolves. Two of the collared cows’ calves disappeared that summer.

“We wondered how many of these GPS-detected wolf-cattle interactions resulted in predations. We looked at the wolf GPS data and compared the tracking logs with locations of known 2009 predation sites. We could see tight spiral patterns in the wolf movements that occurred at those sites. These circling activities may illustrate prey-appraisal or pursuit events,” Clark says.

The following spring (2010), the researchers hiked into sites where spiral patterns occurred in the 2009 wolf track log. Inspecting the sites for signs of predation, they found fresh cattle bones at one of those sites.

Indirect effects of wolves

Clark says earlier research on the direct effects (death and injury losses) due to wolf predation on cattle indicates the impacts are underestimated. Some cattle just disappear; a pack of wolves can consume a carcass overnight.

“However, no one had researched indirect effects of wolf presence on rangeland livestock production. These indirect effects may much more greatly impact livestock producers than death and injury losses. Indirect effects of wolves on livestock range-use patterns impact foraging efficiencies, disposition and stress levels,” says Clark.

Those effects could cascade to affect cattle diet quality, nutritional status and disease susceptibility. Wolf presence also may indirectly affect — and reduce — calf weaning weights and cow body condition in the fall, perhaps resulting in increased veterinary care and supply costs, and death loss to disease.

OX Ranch’s Anderson says he weighs and assesses his cows when they’re collared in the spring before turnout; he does the same when they come off the range to move to winter pasture. Collars are then removed.

“We’re seeing cows come home a full body score less than in the past. With a mature cow, each score is about 100 lbs.,” he explains. This translates into extra feed costs to get cattle through winter.

He says the herd’s conception rate has also plummeted. “With our herd health program, mineral and protein supplement, there’s no reason for this other than the wolves. What normally would be a 90%-95% conception rate in our herd has gone as low as 82%,” Anderson reports.

Besides actual kills, additional animals were severely maimed. “We spend a lot of time doctoring these, and end up with a bunch we can’t sell because they’re crippled,” he says.

In one week of summer 2012, he says nine calves had wolf bites. “The calves may live, but we have to doctor them. We believe the pack’s alpha female is using calves to teach the pups how to hunt,” Anderson says. Four young cows in the first-calf heifer group had big abscesses behind the shoulder and/or above the flank area, due to infected wolf bites. The wolves are playing with these animals.

“We’re also seeing changes in the way cattle are using the range. They bunch up more against fences, which the wolves use to corner them,” Anderson says.

Wolf predation usually stimulates a change in cattle use patterns, Clark says. Anxiety over wolves may prompt cows to shift from high-quality foraging areas to low-quality ones. “Cattle may get up on an open hillside where they can see farther, to detect if wolves

are approaching,” he says.

“Cattle under threat bunch up, standing in open areas where they feel safer,” Clark adds. “These areas become dry and dusty from concentrated trampling, which can lead to respiratory disorders — especially in stressed cattle that are more vulnerable to disease,” he says.

If cattle are being bred on the range, all these factors work toward decreasing the number of cows that get bred on time, or come up open in the fall, Clark says. Late calves alter uniformity of the calf crop, which adversely affects the price received, and may also affect the number or quality of heifers a rancher is able to keep; the future productivity of the herd is adversely affected.

There are also changes in cattle temperament. Cows that were calm and easy to handle become difficult. “In one Idaho herd, a wolf followed cattle down to the calving areas, and the cows were very aggressive trying to protect their newborn calves. The rancher couldn’t tag a calf without being attacked by the mother cow,” Clark says.

Anderson says that before wolves arrived, his cattle were easy to work with dogs. “Our cow boss of more than 25 years has good dogs, and the cattle respected them. Now the cattle chase the dogs, and we can’t use them for herding anymore. Without them, it’s extremely difficult to move cattle in this steep, rugged country,” Anderson explains.

The OX Ranch calves in late May through June, and calves are branded at the fall gathering. “The calves are 350-400 lbs. by that time; when they come into the corral, they’ll size you up and take you,” he says. They’re totally focused on defending themselves, attacking a dog or person.

There also are more handling-related injuries to cattle, along with increased frequency of bunching and flight events, Clark says.

Cattle use of riparian areas

This beef cow is wearing a Clark ATS Plus GPS collar.

The wolf-cattle study has added insight into how cattle use a range area. John Williams, Oregon State University Extension, says data from collared cows have helped answer some resource management questions, including how cattle spend time in a riparian area.

“We’re now collaring more than 80 cattle each year [10 from each study site] and have four years of data. Each study site gives us close to a half-million data points.” he says.

Several graduate students have done masters’ theses on cattle use patterns in riparian areas. “One looked at how much time cattle spend in a riparian area, and found that regardless of where they are on various ranges, cattle spend less than 3% of their time within five meters of the streams,” says Williams.

Another graduate student looked at what cows do while in a riparian pasture. “We put one-second collars on cattle to see how much time they spend eating, lounging, and how much total time they spend within five meters of the creek — and where they cross the creek. They picked about three spots where they go down to the water to drink, and then go back out,” he says.

Data from these studies indicate that range cattle are using riparian areas far less than traditional literature suggests. They generally come in to get a drink and move back to the uplands. If they spend any time near the stream, it’s generally up on the stream terrace and not in the riparian zone, Williams says.

Wolf threat to humans

When wolf numbers are controlled, wolves tend to stay farther back in the high country, says Anderson, manager of the OX Ranch near Council, ID. “When they’re protected, they lose their fear of humans.”

His wife found wolf tracks in fresh snow less than 50 ft. from their house. “We’ve had wolves lie on the county road in the snow at night, next to the corrals, watching cattle under a light at the end of the barn,” he says.

Data from the collared wolf show how close these wolves are coming to homes and human activity. “We have several houses here on the ranch. The collared wolf came within 500 yards of one house 307 times that summer,” Anderson says.

The pack of 12 came within 300 yards of the ranch lodge, and spent all day there. “The people who take care of the lodge have three little boys. The wolves were right above the county road in a little clump of timber, watching the lodge. The collared wolf was there with them, in what we call a ‘rendezvous site.’ ”

A rendezvous site is where wolves park their pups with a baby-sitter wolf while the pack hunts. Dave Ausband, a University of Montana wildlife researcher, has developed a wolf rendezvous prediction-site model. From that, he created a wolf rendezvous site map for the state of Idaho.

“These rendezvous sites anchor the distribution patterns of the entire pack to specific points,” says Clark, a range scientist with USDA’s Northwest Watershed Research Center in Boise, ID.

“Out of curiosity, we plotted our wolf GPS data and our cattle GPS data from one of our Idaho study areas onto Ausband’s map, and found the clusters of concentrated wolf location data lined up with areas predicted on the map as high-quality wolf rendezvous-site habitat,” he says. He says the map and model could help predict where wolf-use patterns and cattle-use patterns frequently overlap.

Wolf rendezvous sites tend to be in grassy areas close to water — not necessarily riparian areas, but meadows without much overhead cover. These areas also happen to be good foraging areas for cattle.

Heather Smith Thomas is a rancher and freelance writer in Salmon, ID.

You might also like:

Cattlemen Protest Wolf Predation Of Cattle In The West

15 Best Photos Featuring Ranch Sweethearts

80+ Photos Of Our Favorite Calves & Cowboys

Ranchers Sing The Praises Of Mob Grazing of Cattle

Feds Move To Delist Gray Wolf Under ESA, Mexican Wolf Remains Protected

You May Also Like