The job of getting heifers pregnant after their first calf starts with nutrition.

March 4, 2015

“Heifers that calve in the first 21 days of their first calving season, on average, remain in the herd a year longer than those that don’t,” says Warren Rusche, South Dakota State University Extension cow-calf field specialist.

“When they calve late as a first-calf heifer, that’s a lifetime disadvantage,” explains Sandy Johnson, Kansas State University Research and Extension beef cattle specialist. “We know those that calve during that first cycle as a first-calf heifer carry that advantage forward, and those cows often have an additional calf in their lifetime than those that calve later.”

Getting heifers to breed back on time — if at all, following their first calf — starts with how they’re developed to breeding time, how much pressure is placed on them to conceive within a short breeding season, bull selection and all of the rest.

However, supposing you’re on the cusp of calving this year’s replacement heifers for the first time; there’s still time to heighten the odds these heifers will breed back and breed back on time.

“Too often, we get heifers bred and think we’re in good shape,” Rusche says. “We need to make sure they maintain body condition and gain condition heading into calving.”

Generally speaking, both Rusche and Johnson recommend that heifers weigh 80% to 85% of their mature body weight at first calving, and have a body condition score (BCS) of 6. By way of comparison, they recommend a BCS 5 for mature cows at calving.

As BCS increases to recommended levels, calving difficulty declines and calf survival increases. Females also cycle and conceive sooner, and milk production and calf weaning weight increase (Figure 1).

Johnson points out that a disadvantage with purchased heifers is having less idea of their ultimate mature size.

Postpartum interval is key

“This period from calving until the cow conceives (postpartum interval) is the most critical period in a cow’s production cycle, and minimizing this time period is important for several reasons,” says Rick Funston, a University of Nebraska beef reproduction physiology specialist. In his paper, “Managing the Postpartum Interval,” Funston says cows that cycle early in the breeding season have higher pregnancy rates than cows that cycle later for several reasons.

“One of the most important is that the cow that cycles earlier has more chances of getting pregnant during a limited breeding season. Keeping other factors constant, such as genetics, age of dam and nutrition, cows conceiving early in the breeding season will have older calves that will have heavier weaning weights,” he says.

In addition, the length of the breeding season influences the uniformity of calves, and therefore influences their value at weaning. “To have a short breeding season, it is vital that cattle cycle early in the breeding season,” Funston adds.

Johnson and Funston co-authored a chapter in the recently published “Management Considerations in Beef Heifer Development and Puberty.” In their chapter, “Post-breeding Heifer Management,” the duo explain that nutrition is key to reducing the postpartum interval (PPI).

“We need to be intentional in developing our rations and intentional in monitoring their weight and body condition,” Johnson says. “We know when their needs are expected to change because of when they were bred. It’s too common for time to sneak up on us.”

Johnson says heifers have increasing nutritional needs during the third trimester, a time in a spring-calving system that forage quality typically is decreasing. “Then the weather sneaks up on us. Those heifers can start losing weight at a time when adding weight is critical and expensive,” she says.

Moreover, Funston and Johnson explain, “Forage intake in pregnant heifers decreases as gestation advances, which could affect gain and energy intake during the third trimester. Continued gain is needed through calving for heifer and fetal growth, particularly in more moderate development systems.”

Subscribe now to Cow-Calf Weekly to get the latest industry research and information in your inbox every Friday!

With that in mind, Johnson recommends feeding an ionophore to heifers and cows. She explains, “An ionophore gives cows and heifers more energy per mouthful, particularly in late gestation and early lactation, to optimize what she can get out of the forage.”

That doesn’t mean making them pig-fat. Johnson and Funston explain cows with a BCS greater than 7 have lower pregnancy rates and more calving difficulty than cows at BCS 5 to 6.

“Don’t overfeed them,” Johnson says. “But do have enough condition at calving to account for the fact that we don’t often have the quality of feed many of these heifers need for the lactation potential they have.”

In other words, after calving, providing adequate nutrition is typically the challenge, rather than providing too much.

“Heifers fed diets deficient in energy or protein during the last trimester experience more calving difficulty, conceive later in the breeding season, and have increased sickness, death and lower calf weaning weight,” Funston and Johnson say. “Although dietary restrictions during early heifer development may reduce cost and capitalize on compensatory gain, continued restriction through subsequent winter [gestation] periods increases the proportion of non-pregnant heifers and reduces herd reproductive rates.”

Hopefully, the worry about over-feeding heifers ahead of calving isn’t as widespread as it used to be, Rusche adds. This common myth runs along these lines: Reduce feed intake in the last trimester and you reduce calf size, which decreases calving problems. Though it might sound logical, the opposite is true.

“Too often, we rely strictly on our eye to gauge progress. This day and age, we need to be using a scale,” Johnson says. “We also tend to think we can remember what condition a heifer was in at what time, so we don’t need to weigh them or record it. I find that I miss what they weigh with my eyes, and that time tends to get away from me.”

Provide separate management

Nutrition and the fact that first-calf heifers are still growing are key reasons why these folks encourage producers to manage first-calf heifers separately from mature cows.

“We have to realize that first-calf heifers will have a longer PPI. That’s why we need to breed them in advance of the mature cows and utilize a relatively short breeding season,” Johnson says. She defines a short season as 45 days, but prefers 30 or less.

“First-calf heifers always take longer to resume cycling. They may take anywhere from two to three weeks longer than their mature cow-herd counterparts if they’re getting all they need to eat, and even longer if they’re not — which is often the case,” Johnson explains. “Even if heifers are bred three weeks ahead of the mature cows, if the heifer calves on day 60, she hardly has a chance to be cycling in time for the next 60-day breeding season.”

BEEF Seedstock 100

Looking for a new seedstock provider? Use our BEEF Seedstock 100 listing to find the largest bull sellers in the U.S. Browse the Seedstock 100 list here.

For a cow to calve at the same time every year, Johnson points out the female has 82 days to rebreed after calving. “A typical cow with adequate nutrition takes about 50 days to start cycling again, while a first-calf heifer will take closer to 70 days,” she says. “Therefore, producers should consider breeding and calving first-calf heifers before the mature cow herd.”

Timely calving assistance

Calving time itself offers further opportunity to hedge bets for getting first-calf heifers to breed back on time.

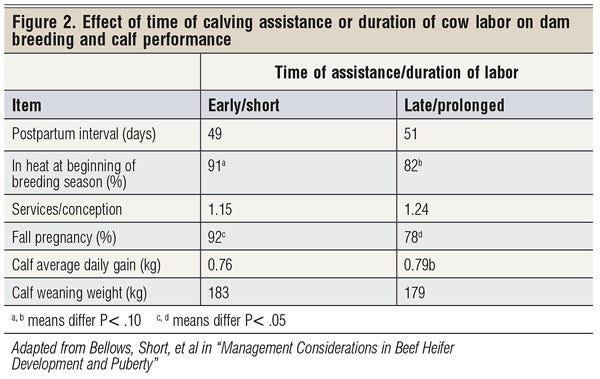

“Time of intervention, when obstetric assistance is needed, affects resumption of the estrus cycle,” say Johnson and Funston. “Dams provided with early assistance had a higher percentage in estrus by the beginning of the breeding season, increased fall pregnancy rate and improved calf gains, compared to late-assistance dams” (Figure 2).

In other words, Johnson explains, delayed calving assistance contributes to a longer PPI.

“When we add up all the costs associated with calving difficulty, including death loss, veterinarian and labor expenses, plus the potential for lowered reproductive success, it’s very clear that calving difficulty in heifers is an expensive proposition — even more so in today’s market,” Rusche says. He provides additional insight in his article, “How Does Calving Difficulty Affect Reproduction for Next Year?”

“While we can’t do anything to change the genetics in place for this year’s calf crop, we can put plans in place to maximize our chances for success during calving season this year,” Rusche says.

His recommendations include:

• Be prepared. Have the facilities and all necessary equipment ready and available in plenty of time.

• Have a plan. Think about what could go wrong during calving season and how you can address those problems.

• Recognize when you may need to call for a veterinarian’s assistance. Waiting too long can greatly cut your chances of success.

• Sanitation is important, but often overlooked. “Anytime we’re assisting the calving process, we’re introducing pathogens into the reproductive tract. Some steps we can take include cleaning the cow before entering, using obstetrical sleeves and disinfecting the equipment after use,” he says.

Both Rusche and Johnson encourage using expected progeny differences (EPDs) for Calving Ease-Direct as an indicator of the trait, rather than the birth weight EPDs or actual birth weight.

“Our birth-weight EPDs are no longer the most accurate tool to use for calving ease,” Rusche says. “I don’t care what a calf weighs at birth; I care about whether or not I had to pull the calf.”

Along with Calving Ease-Direct, Johnson says, “If I have an opportunity to select sires for first-calf heifers, I want to also consider Calving Ease-Maternal in creating my replacement heifers.”

For that matter, Johnson also points out that using bulls with lower milk EPDs could help producers keeping replacement heifers from those sires achieve a more sustainable level of herd milk production.

Johnson recommends that producers provide their highest-quality forages to the cow herd after calving and through breeding. But, she adds that even high-quality forage may be unable to support herd milk production that is too high for the environment.

“Cows will first use available nutrients to produce milk, and if nutrient intake is in excess of milk production, then they can put nutrients towards reproduction,” Johnson explains. “If cows are bred to produce a high quantity of milk, reproduction is delayed until the cow is consuming more energy than she needs to produce milk, or reaches a positive energy balance.”

The bottom line

No one likes to cull cows due to reproductive failure, but being forced to cull first-calf heifers because they won’t breed back or breed back on time comes with extra economic sting.

“A first-calf heifer that either loses her calf or fails to rebreed could easily lose half her value when she’s marketed as a cull, compared to being retained on the balance sheet as a bred female,” Rusche says. “For example, if that bred heifer cost $3,000 and is culled for $1,500, we haven’t covered her cost. Genetically, she should represent the best we have, too. So, we lose a tremendous amount of opportunity.”

If you’re not looking for it, Rusche adds that it can be too easy to overlook the depreciation cost associated with cows that must be culled early.

Johnson points out that calves born in the first 21 days of the calving season are often the heaviest in their contemporary group at weaning, and that advantage often carries through to harvest, if the producer retains ownership.

She adds that a defined and shorter breeding and calving season can help producers time vaccinations more accurately. Tightening the season also reduces the variation in nutritional requirements within the herd at any one point in time, which can help save time and money on herd inputs.

Johnson suggests that producers consider keeping a few extra replacement heifers in their system so they’re able to rebuild the herd, while keeping the option open to cull those that breed late.

“Use a timely pregnancy diagnosis and strict culling means telling yourself, ‘She’s pregnant, but she’s late. I’m going to market her in a bred-cow market, but she’s not going to stay in my herd,’ ” Johnson says.

“Every calf and every bred female are worth more dollars today than ever before,” Rusche says. “Small improvements in outcomes will have a much larger financial impact than we’ve seen before.”

Some considerations when purchasing heifers

“Too often, after we cull the freeloaders, we can’t cull for anything else and maintain the herd size,” says Warren Rusche, South Dakota State University Extension cow-calf field specialist.

“Preventing calf death loss at calving from calving difficulty, disease or environmental stress is the obvious place to start when we’re trying to increase our income and minimize our need for replacements,” he says. “The effect that calving difficulty has on rebreeding success of a first-calf heifer isn’t always so obvious.

In fact, in a Meat Animal Research Center study, the conception rate during a 70-day breeding season for heifers that had trouble calving was 16% lower, compared to heifers that calved unassisted (85% versus 69%).

Data, such as those collected through the National Animal Health Monitoring Service, indicate that reproductive failure is the leading reason beef cows and heifers are culled, followed by cow age. Moreover, the females mostly likely to be open are heifers nursing their first calves.

“We need to do everything we can to maintain herd size, reduce capital requirements and give ourselves the opportunity to expand, while culling for reasons other than reproductive failure,” Rusche says.

In other words, broader culling latitude revolves around cows and heifers breeding on time, calving on time and breeding back on time.

That’s one impetus producers have for purchasing bred heifers, rather than developing and breeding their own. Rusche says the economics can lean toward buying heifers when the real costs of developing heifers are considered — everything from development costs, to having fewer productive cows to run, to maintaining a bull for the yearlings and one to create replacements.

Of course, buying heifers comes with plenty of baggage, too.

For one thing, Sandy Johnson, Kansas State University Research and Extension beef cattle specialist, points out it’s difficult to project the ultimate mature size of purchased heifers — critical for accurate nutrition and breeding management — without knowing that of the dam.

“The hardest part of buying heifers is finding out how they’ve been managed,” Rusche says. “When we buy heifers, we’re investing a lot of money. I’d like assurance about how’s she’s been managed and how much effort has been made in sire selection.

“Communicate with sellers to find out how the heifers have been managed. Are they the first cut or the last cut? What are the sires of the heifers, and what are the sires of the calves the heifers are carrying?” He adds that ultrasound provides an opportunity to identify heifers accurately that should calve within a narrow window of time.

Health and immune status are other obvious reasons to communicate with sellers more effectively.

“What kind of forage situation is she coming out of?” Johnson asks “And, what kind of forage situation are we placing her in? Grazing is a learned experience.

“Do we know the mineral program she’s coming from?” she asks. “If in doubt, assume it wasn’t adequate and provide one that is.

“Plan and isolate,” Johnson says. “When we bring cattle into an operation, it’s not always the threat of exposing the current herd, but also the threat of what we’re exposing the new purchases to with the current herd.”

You might also like:

7 U.S. cattle operations honored for stewardship efforts

How Schiefelbein Farms made room on the ranch for nine sons

Prevention and treatment of cow prolapse

Photo Gallery: Home is where you hang your hat

World's largest vertically integrated cattle operation

8 tips for being a better ranch manager in 2015

15 photos of cowboy hats in action

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like