The FDA’s recent decision regarding the use of feed-grade antibiotics in livestock production could be a positive for cattle producers, specialists say.

January 24, 2014

If you read the popular press headlines following the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) announcement in December regarding the use of feed-grade antibiotics in food animal production, it was easy to get the notion that feed-usage antimicrobials were being all but banned.

Instead, the Veterinary Feed Directive (VFD) announcement preserves the use of medically important feed-grade antibiotics in food animal production for only the prevention, control and treatment of specific disease-causing bacteria. FDA is asking pharmaceutical companies to remove, voluntarily, any label indications for growth promotion.

Dee Griffin, feedlot production management veterinarian at the Great Plains Veterinary Educational Center in Nebraska, uses generic tetracycline to illustrate the point. Today, the “Indications For Use” section of the label might say, “For increased rate of body weight gain and improved feed efficiency.” After a three-year transition period, because pharmaceutical companies have removed such language voluntarily — or, presumably, because of subsequent regulatory action — that won’t be allowed.

Instead, for the very same product, Griffin explains the “Indications For Use” section of the label could read: “For reduction of incidence of liver abscesses in beef cattle associated with Fusobacterium necrophorum and Arcanobacterim pyogenes.”

Mike Apley, DVM, Ph.D., and a professor in clinical sciences at Kansas State University, explains restricting the use of antibiotics in food animal production to assure animal health is the first principle outlined in guidance from FDA in April 2012.

That’s one reason Griffin and Del Miles, a DVM with Greeley, CO-based Veterinary Research and Consulting Services (VRCS) LLC, believe cattle producers will see little impact from the FDA announcement. Producers already use feed-grade antibiotics to prevent, treat or control specific disease-causing bacteria, rather than to enhance production, specifically.

Subscribe now to Cow-Calf Weekly to get the latest industry research and information in your inbox every Friday!

Moreover, some in the industry are already working to use antibiotics less. Miles says VRCS, for example, began a concerted effort three years ago to utilize management to decrease antibiotic use. It saves customers money while addressing consumer concerns. He adds that the VFD also provides the industry with further documentation of its judicious antibiotic use.

The VFD represents the second FDA principle outlined in April 2012: the use of medically important antimicrobial drugs in food-producing animals should be limited to uses that include veterinary oversight or consultation.

“This means that the remaining uses of medically important antimicrobials in the feed and water of food animals [prevention, control and therapy] will require authorization by a veterinarian through a veterinary feed directive,” Apley explains.

“Other than the extra paperwork, I think this is a step in the right direction for the industry,” Miles says. The added paperwork is due to the VFD.

Potential for new products

Another reason that producers should notice little impact is that the FDA announcements in April 2012 and December 2013 came as no surprise.

In fact, Griffin explains it’s the final step in a journey that began two decades ago. At the time, commonly used drugs such as tetracycline were becoming less effective in treating cattle health challenges like pneumonia. Meanwhile, antibiotic resistance to them was increasing, because the doses allowed by the label were too low to be effective. Producer and veterinary organizations began working with FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM) and Congress to allow the extra-label use (ELU) of these antibiotics.

“This legislation, for the first time, allowed livestock to receive the proper dose of an animal drug regardless of the dose prescribed on the label,” Griffin explains. “This legislation has played an integral part in not only improving the proper antibiotic dosing in livestock, but helped pave the way to a better understanding of how to properly assign withdrawal times for drugs in which the ELU applied.”

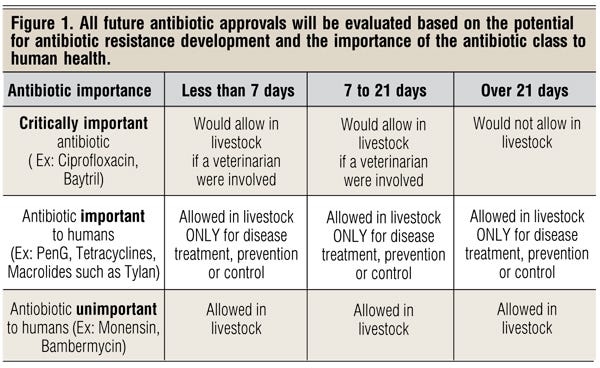

Next, Griffin says there was almost a decade of work between FDA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to better understand the origin and trends of antibiotic resistance. One result of that process was a grid classifying antibiotics as critically important, important or unimportant to human medicine (Figure 1).

Critically important antibiotics can only be used in livestock for specific reasons under veterinary supervision, and cattle cannot be treated with the antibiotic for longer than 21 days. Those classified as unimportant to human medicine — ionophores as an example — have no time restriction and can be used without veterinary supervision. FDA’s recent announcement focuses on the category in between — those classified as important to human medicine, such as chlortetracycline, oxytetracycline and tylosin.

Along with providing veterinary supervision and documentation of the feed usage of these medically important antibiotics, Griffin says the process makes possible the approval of new feed-grade antibiotics.

“Livestock producers were stuck with the antibiotics that had been approved,” Griffin says. “Nothing new was going to be available to help manage health problems in livestock unless the FDA CVM figured out a mechanism by which the antibiotic could be used without jeopardizing the safeguards needed to protect humans.”

The mechanism turned out to be the VFD, something common in the swine industry but unused for cattle antibiotics until tilmicosin (Pulmotil®) was approved for use in cattle feed in 2011.

“The VFD represented a way that FDA could approve an antibiotic for use in livestock feed to treat, prevent or control a specific disease-causing bacteria in a targeted group of affected animals, or in a group of animals at a high risk of developing a disease caused by a specific bacteria,” Griffin explains.

The American Veterinary Medical Association and some pharmaceutical companies were quick to voice support for the new FDA guidance.

“This action promotes the judicious use of important antimicrobials to protect public health while ensuring that sick and at-risk animals receive the therapy they need,” says Bernadette Dunham, DVM, Ph.D., director of the FDA CVM.

“A decade from now, if antibiotic resistance has decreased, we will all be glad we participated in helping the effort,” Griffin says. “If antibiotic resistance doesn’t change, the world will know the problem they blamed on us wasn’t of our making. And we will likely have gotten a few new feed-usage antibiotics that are much more effective than what we’ve had available without a VFD. It seems to me it’s perhaps a win-win for us.”

You might also like:

3 Lessons From A Greenpeace Dropout

True Or False: Animal Agriculture Uses 80% Of All Antibiotics

Antibiotics: Whats Your Responsibility?

20 Dick Stubler Ranch Life Cartoons

Animal Antibiotics Resistance & Human Health

More Consumers Are Realizing The Dishonesty Of The Animal Rights Industry

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like